8 Women Artists Using Ceramics to Subvert Art Traditions

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Untitled, 2021. Photo by Greg Carideo. Courtesy of the artist and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York.

Christabel Macgreevy, Sankofa Bird with Silver Egg, 2022, Tristan Hoare

The field of ceramics is evolving. In recent years, the medium has garnered new mainstream interest and acclaim. Meanwhile, women artists are seeing long-overdue engagement with their work. As their medium evolves, female artists, both emerging and established, are exploring the versatility of clay.

Here, we focus on eight artists who criticize the hierarchies that delegate female ceramicists and their work to the periphery. Ceramics have been regularly sidelined in the history of contemporary art. In 1941, critic Clement Greenberg introduced his concept of “the decorative,” which carried negative associations with femininity and craftwork—the opposite of the ideal modernist aesthetic. And, as Louise Bourgeois noted in 1979, “When you work in the school of abstraction, you have to avoid…the decorative.” Today, female artists are working to bridge the barrier between the nonfunctional sculptural object and the functional craft object. Their vessels are often warped, asymmetrical, and uncanny—even, sometimes, creating imitations of the mundane.

The hyper-tactile vessels made by these women rail against aesthetic perfection, debating the traditional role of women in the art world as mere objects of visual admiration. Paralleling emerging trends toward figuration in contemporary painting, artists place a faux-naïf style in dialogue with the grotesque to depict the female form. The grotesque, as outlined by art historian Frances Connelly in “The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture” (2012), can “spring from its maker’s free imagination, unfettered by rules of design or canons of beauty.” Clay, a craft material on the outskirts of fine art, is an apt medium for artists intending to transgress boundaries.

Recent exhibitions have drawn attention to this trend for craft figuration and the imperfect in contemporary ceramics. Last year, “Strange Clay” at the Hayward Gallery highlighted the medium’s growing plasticity, while the current exhibition “Funk You Too!” at the Museum of Art and Design (MAD) in New York traces the growing trend for what curator Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy calls the “aesthetic of optimism.”

Today, the beguiling medium of oddball ceramics offers a starting point for those looking for something more than the perfunctory vessel.

Ruby Neri, B. 1970, San Francisco. Lives and works in Los Angeles.

Ruby Neri, Untitled, 2018, Galeria Mascota

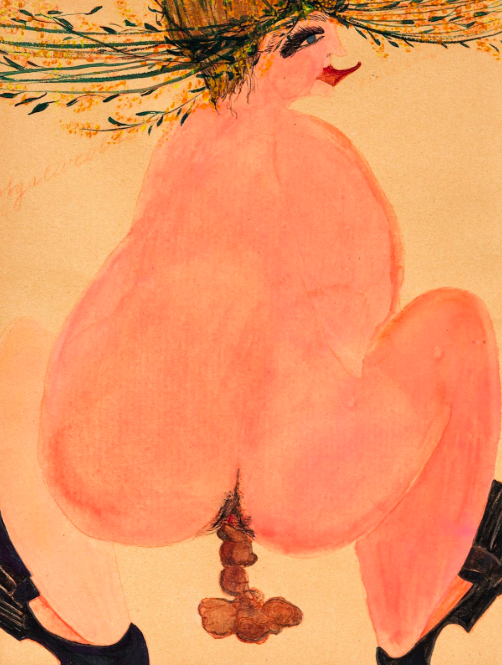

In Ruby Neri’s work, the human body is a harbinger of desire and repulsion. Her work features in “Funk You Too!,” a reinterpretation of a 1967 exhibit in which her father, Manuel Neri, also participated. Ruby Neri is a forerunner of what MAD’s deputy director Elissa Auther labeled as a new generation of Funk ceramic artists.

Untitled (2018), for example, speaks to the artist’s nontraditional technique. A misshaped ceramic vase is anthropomorphised into the naked figures of two women, their lips and nipples rouged, akin to a Schiele nude. By applying spray-based glazes onto her pieces, Neri combines the effervescent effect of watercolor with the solidity of a decorative vessel.

Ruby Neri, Revelations, 2022, David Kordansky Gallery

Ruby Neri, Past Present Future, 2022, David Kordansky Gallery

Neri is increasingly known for large, floor-based vases and wall-mounted ceramic sculptures, like Past Present Future (2022) and Mamma (2021), which equally reference 1980s riot grrrl bawdiness and prehistorical representations of the female body. These works accentuate anatomical zones—visually paralleling handheld female statuettes and fertility charms, such as the Venus of Willendorf. Neri’s work is singular, using ceramic to build the monumentally feminine while retaining the tactile associations of craftwork.

Sally Saul, B. 1946, Albany, New York. Lives and works in Germantown, New York.

Sally Saul, Bewildered, 2022. Courtesy of Venus Over Manhattan.

Sally Saul, Bewildered, 2022. Courtesy of Venus Over Manhattan.

Artist Sally Saul had been working in ceramics for over 30 years without critical recognition before recently experiencing a reappraisal from the contemporary art market. “Sally Saul: Knit of Identity” at Rachel Uffner Gallery in 2017, the artist’s first solo show in New York, received wide acclaim. In 2022, she was added to the roster of Venus Over Manhattan. Originally turning toward clay via San Francisco’s Funk movement, Saul refrains from showy ostentation in her work, with presidents, saints, and the natural world all depicted with the same equitable honesty.

Sally Saul, Sultry Day, 2022. Courtesy of Venus Over Manhattan.

Sally Saul, Sultry Day, 2022. Courtesy of Venus Over Manhattan.

Regarding the pieces featured in “Knit of Identity,” Saul wrote: “Memory, or an editing of memory, informs several of my pieces…fragments that evoke a time and place, refuge, physicality, and act as a talisman.” In Bewildered and Sultry Day (both 2022), Saul creates Botero-esque silhouettes, employing a faux-naïf figuration to depict the human form. Saul’s most recent ceramic figurines are melancholic, reflective of the environmental destruction described in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). Often open-mouthed and animated, the works are active guides through Saul’s constructed world.

Brie Ruais, B. 1982, Southern California. Lives and works in New Mexico.

Brie Ruais, Intertwining Bodies, Roots, Hair (130lbs times three), 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Cooper Cole, Toronto.

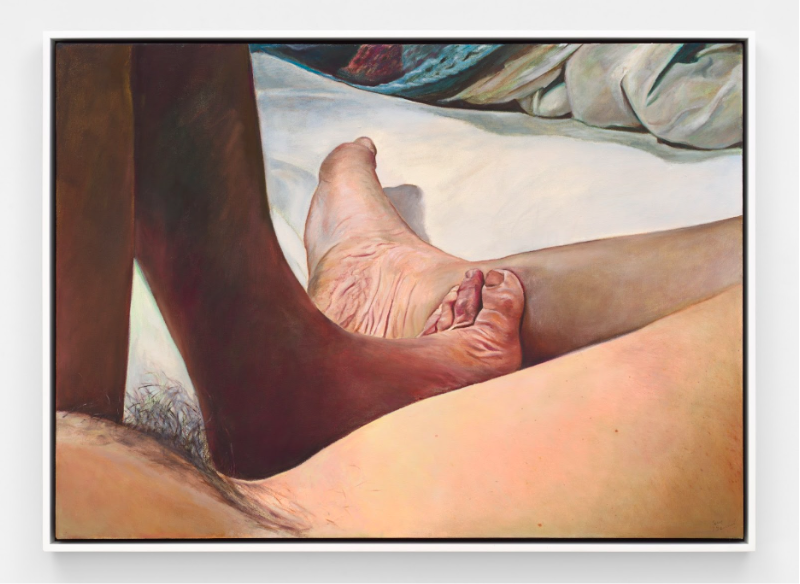

Brie Ruais’s work expands the notion of corporeally oriented ceramics. “The sculptures tap into the body’s knowledge as opposed to the mind. I let the body and clay lead,” Ruais said in the press release for “Some Things I Know About Being In A Body,” her 2021 solo show at Albertz Benda. This tenet is expressed best in Intertwining Bodies, Roots, Hair (130lbs times three) (2022), which was featured in the Hayward Gallery’s exhibition “Strange Clay.”

The tactile imprints which form the limbs of Ruais’s sculpture deliberately recall the artist’s movements while mining for materials in a clay quarry, recorded in the triumphal video art piece Digging in, Digging Out (2021). Engaging, embedding, and emerging from the wet, raw earth, the artist then repeats these excavation marks in the studio, impressing her exact body weight into foraged clay. The marks of the artist’s clawing hands are then fired and painted, as in Spreading Outward from Center, Blue Eye (2022). These intensely expressionistic, wall-mounted pieces portray the future and cross-medium potentiality of clay work. Ruais’s latest work is featured in a solo show at Night Gallery in Los Angeles through June 24th.

Alake Shilling, B. 1993, Los Angeles. Lives and works in Los Angeles.

Alake Shilling, installation view of “A Bug's Life” at Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles, 2023. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of Jeffrey Deitch.

Alake Shilling has stated she hopes the viewer of her works will become an “accessory of comfort.” In her reinterpretation of plush toys, Shilling invokes memories of a simpler time. Childhood has always been a source of creative inspiration for the artist—yet Shilling’s works are never saccharine. Instead, they conjure a sense of displacement in the viewer. In the book Alake Shilling: The Hippest Trip in America—By Land, Air and Sea (2023), the artist displays images of her relatable source material: Disney cartoons, children’s animations, and memes. Works like Jolly Bear (2021) are uncanny: totally monochromatic versions of their original inspiration. On a recent podcast, the artist said that she intends for her sculptures to create a universal experience, striving to capture both pleasure and pain.

Alake Shilling, installation view of “A Bug's Life” at Jeffrey Deitch Los Angeles, 2023. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch.

A solo show at Jeffrey Deitch’s Los Angeles space, “A Bug’s Life,” debuts a new series of Shilling’s works. The artist cites inspiration from animal totems in the traditional mythology of Yoruba culture, combined with an aesthetic influence from the stationery brand Lisa Frank. Works like Snelly Boop (2019) are animistic, grotesque explorations of this ultra-positive commodified reverie.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, B. 1929, Caracas, Venezuela. Lives and works in Venice, California.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Tile Table, c. 1990. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy of the artist and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York.

Magdalena Suarez Frimkess’s unusual objects recycle mass-produced images. Having worked in clay since the 1970s, the artist draws upon many influences, from Peter Voulkos to Toulouse-Lautrec, Zuni patterns, and Betty Boop. In her tile pieces, she transposes episodic elements from comic strips, using the stylized patterns of Hispano-Moresque tiles. Frimkess is as likely to use a delft blue pigment, traditional in Northern European pottery, as she is to mimic a vessel representing a Mesoamerican deity.

Throughout her life, Frimkess has continually returned to the comic folklore figure of Condorito. The Chilean comic book hero exposed society’s hypocrisies and made his popular debut in 1949, the same year Frimkess relocated to Santiago. “I tell everyone he’s my philosopher,” the artist said in a 2020 interview with Michael Ned Holte for Mousse Magazine.

Frimkess’s skill is her ability to conjoin modern folklore in wry, politically conscious picaresque narratives, as in Cup in Spanish (2010). Distorted figurines of Mickey and Minnie Mouse, depicted as wary and a little bewildered, are Frimkess’s most famed works. In 2024, the artist’s work will be the subject of a major retrospective at LACMA.

Christabel MacGreevy B. 1991, London. Lives and works in London.

Christabel Macgreevy, Witch Bottle (White Hellebore for the Humours), 2023, Tristan Hoare

Christabel Macgreevy, Witch Bottle (Adonis Vernalis & Pheasant's Eye), 2023, Tristan Hoare

Christabel MacGreevy’s objects are imbued with ritual. In “Sexing the Cherry,” a dual show with Rafaela de Ascanio at Tristan Hoare, asymmetrical vases contain literary and historical references. Works like Witch Bottle (White Hellebore for the Humours) and Witch Bottle (Adonis Vernalis & Pheasant’s Eye) (both 2023) critique the historical mystification of female healing practices.

Women folk healers were, as Silvia Federici wrote in Caliban and the Witch (2004), subject to persecution as witches with the advent of early-modern capitalism. MacGreevy depicts these forgotten subjects alongside other decisive female figures, such as Salome I (2023), who is shown in graphic applique carrying the head of John the Baptist. In works like Ace of Hearts (2023), a figure wraps around a vase, fluid and nonconforming.

Lindsey Mendick, B. 1987, London. Lives and works in Margate, England.

Lindsey Mendick, Potato Head, 2021, Cooke Latham Gallery

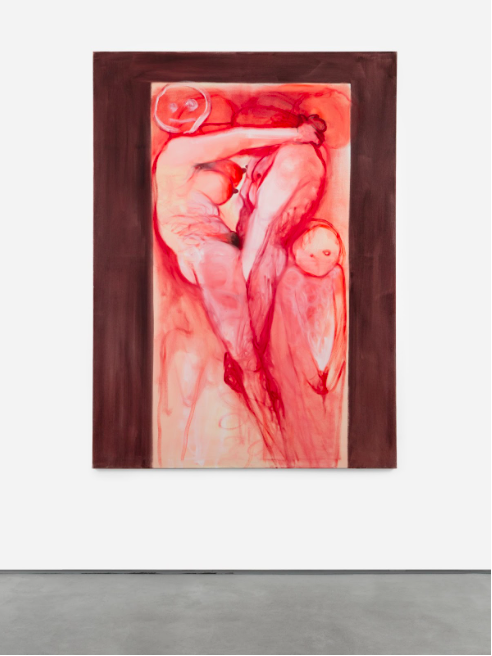

Lindsey Mendick’s 2022 debut show at Carl Freedman Gallery, “Off With Her Head,” introduced the artist’s Rabelais-esque artistic method. In fully immersive installations, Mendick’s ceramic pieces are not merely exhibited, but rather, they perform. In I Drink To You Tracey (2022), Tracey Emin’s piece Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996) is portrayed as tableaux, presented to the viewer within a box.

Meanwhile, in I Drink To You Europa (2022), the mythological tale of rape is subverted. Presented as a camp, ceramic candelabra flickering in the darkened gallery, the sculpture is both functional and nonfunctional. Mendick depicts Europa in a moment of rapture, receiving oral sex from Zeus disguised as a bull.

The artist’s brilliance is similar in her more abstract works. In Bursting at the Seams (2021), bulging eyeballs protrude unexpectedly from the delicate, reflective surface of the glazed ceramic—a playful, grotesque interpretation of the traditional vessel.

Diana Yesenia Alvarado, B. 1992, Los Angeles. Lives and works in Los Angeles.

Diana Yesenia Alvarado, Orejas, 2019. Photo by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of the artist and The Pit.

Diana Yesenia Alvarado, Cometa Verde (Caterpillar ser), 2021, Galeria Mascota

The past year has been eventful for ceramic artist Diana Yesenia Alvarado. Her work Lista Para Volar (2022) was part of “Funk You Too!” and the artist is in residence at Cerámica Suro in Guadalajara, Mexico.

Alvarado’s sculptures function as mnemonic devices, devised to capture the sounds, smells, colors, and overall sensations of a predominantly Latinx neighborhood in Los Angeles, where the artist was raised. These sculptures are vibrant and psychedelic, creating a cinema of sensation. In Mezkalita (2020) and Cometa Verde, Caterpillar ser (2021), colors bleed and meld, a product of the artist’s desire to allow her materials a life of their own.